On Overthinking

Original by Michel de Montaigne

Translated/Adapted, from the French, by Camille Uglow

Comme Nostre Esprit S’empesche Soy-mesmes

C’est une plaisante imagination, de concevoir un esprit balancé justement entre-deux pareilles envyes. Car il est indubitable, qu’il ne prendra jamais party: d’autant que l’application et le choix porte inequalité de prix : et qui nous logeroit entre la bouteille et le jambon, avec egal appetit de boire et de manger, il n’y auroit sans doute remede, que de mourir de soif et de faim. Pour pourvoir à cet inconvenient, les Stoïciens, quand on leur demande d’où vient en nostre ame l’election de deux choses indifferentes (et qui fait que d’un grand nombre d’escus nous en prenions plustost l’un que l’autre, n’y ayant aucune raison qui nous incline à la preference) respondent, que ce mouvement de l’ame est extraordinaire et desreglé, venant en nous d’une impulsion estrangere, accidentale, et fortuite. Il se pourroit dire, ce me semble, plustost, que aucune chose ne se presente à nous, où il n’y ait quelque difference, pour legere qu’elle soit : et que ou à la veuë, ou à l’attouchement, il y a tousjours quelque choix, qui nous tente et attire, quoy que ce soit imperceptiblement. Pareillement qui presupposera une fisselle egallement forte par tout, il est impossible de toute impossibilité qu’elle rompe, car par où voulez vous que la faucée commence ? et de rompre par tout ensemble, il n’est pas en nature. Qui joindroit encore à cecy les propositions Geometriques, qui concluent par la certitude de leurs demonstrations, le contenu plus grand que le contenant, le centre aussi grand que sa circonference : et qui trouvent deux lignes s’approchans sans cesse l’une de l’autre, et ne se pouvans jamais joindre : et la pierre philosophale, et quadrature du cercle, où la raison et l’effect sont si opposites : en tireroit à l’adventure quelque argument pour secourir ce mot hardy de Pline, solum certum nihil esse certi, et homine nihil miserius aut superbius.

Camille Uglow obtained her bachelor’s degree in Literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is currently a PhD student in the Literature Department at the University of California, San Diego. Her research interests include early modern French and English literature and culture, Shakespeare, and early modern drama.

Michel de Montaigne is best known for creating the modern essay. He was born into a wealthy bourgeois family in 1533. Eventually, his family attained noble status after his father fought in King Francis I’s army. Shortly after his father passed, he fell into a deep melancholic state and began writing his essays as a way to self-reflect and vocalize his thoughts. These essays were mere attempts to ‘assay’ the value of himself, his nature, his habits, and his own opinions as well as those of others. They hunted for truth and knowledge of humanity, and explored his reactions to his readings, travels, and experiences in peace and in tumult.

Translator’s Note:

A little over four centuries after Montaigne’s Les Essais were initially published, scholars, students, and casual readers alike continue to read Montaigne’s work. His highly introspective writing serves as a window into his thoughts, sentiments, and experiences, and simultaneously foregrounds self-reflection, skepticism, and humanism. In a fast-paced world showing no signs of slowing down, his words continue to have the power to resonate with readers even now. However, because of the restless nature of our world today, there are few opportunities for us to self-reflect. His skepticism is particularly relevant to our present time, as he reminds us not to accept everything at face value. In this digital age, where we are constantly bombarded with the opinions and judgments of others, engaging in introspection is vital to gaining a deeper understanding of ourselves. It is crucial to do so now more than ever, as people are experiencing higher rates of identity struggles, anxiety, depression, body image issues and other related challenges. I translated the title “Comme Nostre Esprit S’empesche Soy-mesmes” to “On Overthinking” because overthinking, along with other anxieties, are common struggles for many people today. This title allows Montaigne’s essays to resonate more powerfully with a twenty-first-century audience.

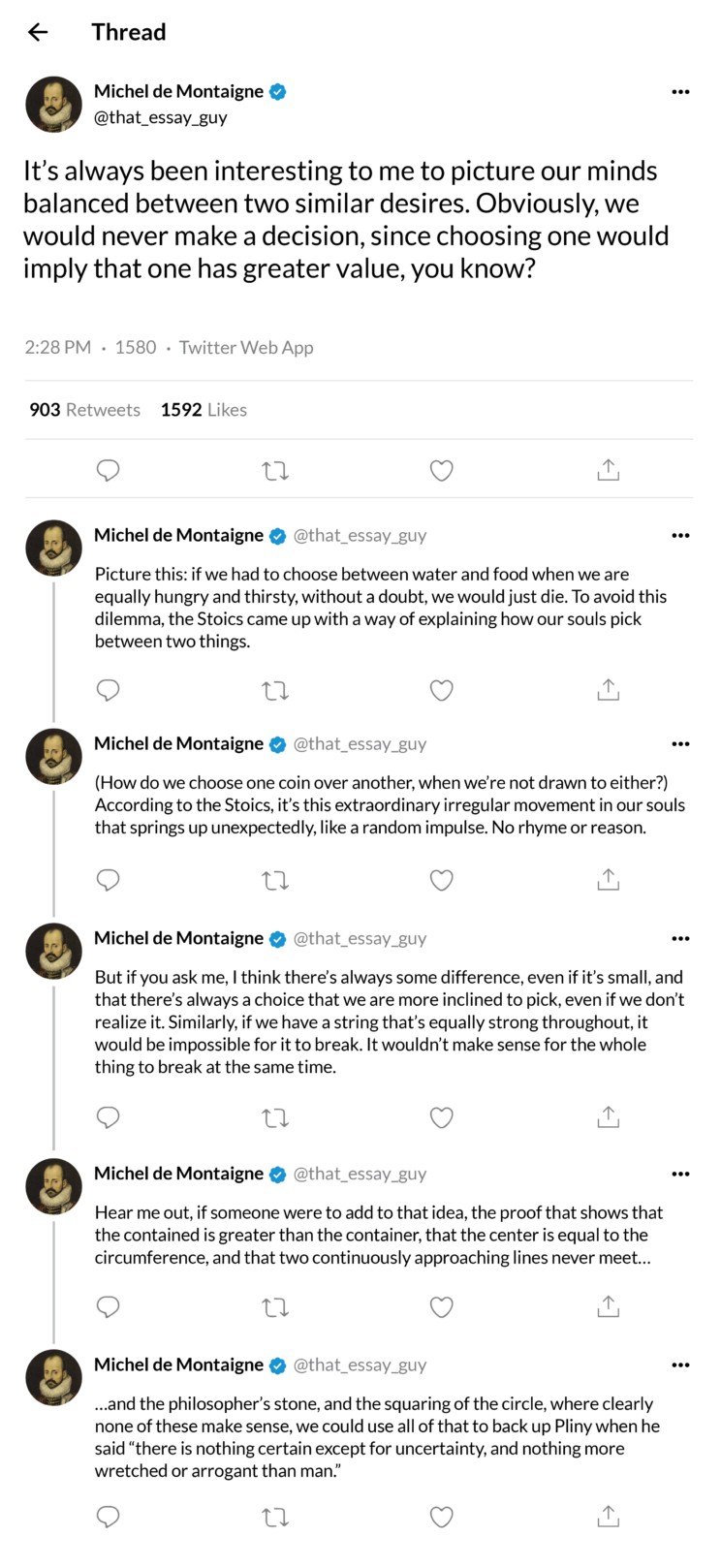

Montaigne was the first to adapt the French word essai, meaning a try (from the verb essayer, meaning to try) into a form of writing. The title of his works alludes to his intention for writing—a mere attempt, an exploratory journey across a multitude of topics. Like Montaigne’s Essais, my translation is an attempt to act as a bridge between Montaigne’s words and the contemporary audience. Given that a great deal of our lives revolve around technology and social media, I felt that creating a social media mock-up for Montaigne would be appropriate. His stream-of-consciousness writing style is similar to that of a Twitter thread today. With the most recent celebrated translation of Montaigne’s essays being written in 1987 (1), the time has come for a lighter, more colloquial and playful twenty-first-century interpretation.

(1) M.A. Screech, Michel de Montaigne—The Complete Essays, (Penguin Books, 1987 p. XV).