PORTALS: A LEXICON OF A FANTASTICAL PHILIPPINE REVERIE

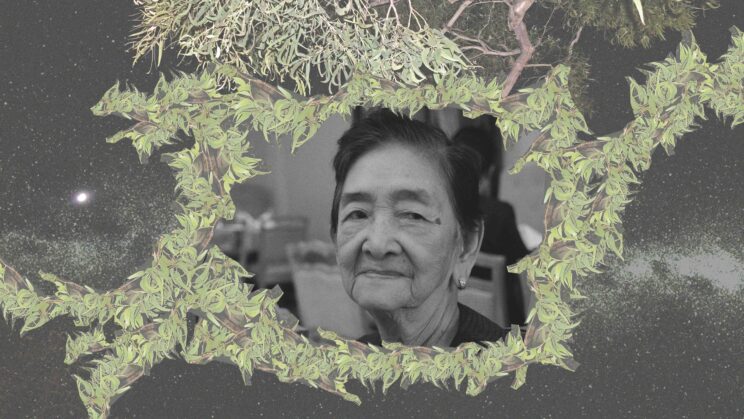

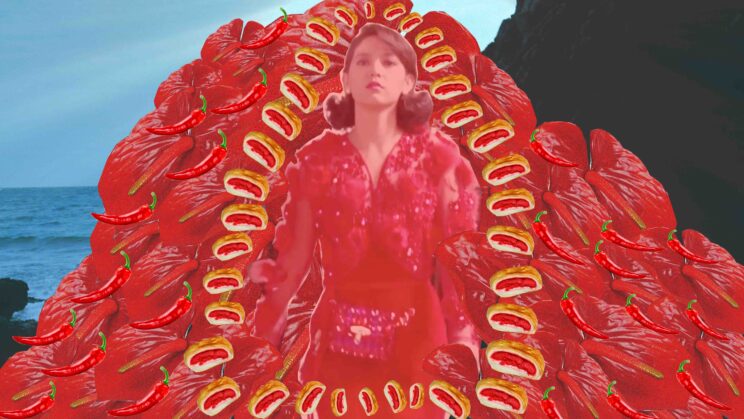

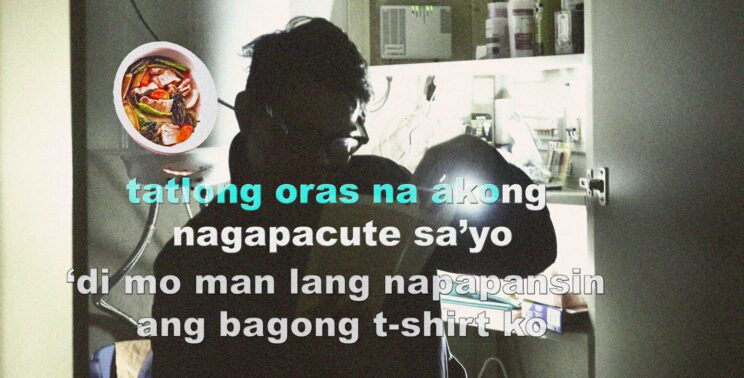

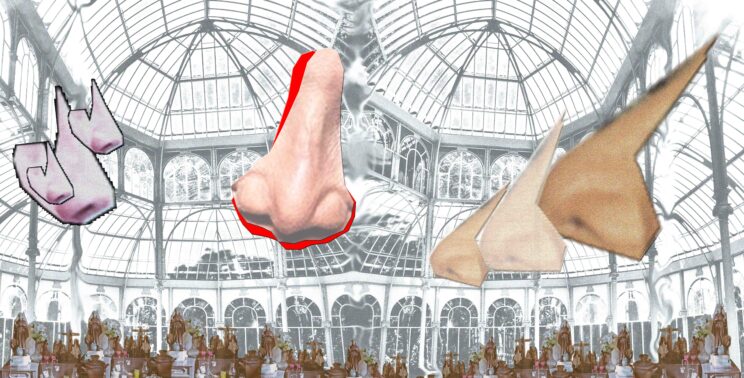

A visual art series by Gian Cruz and Gisela Marcelang

Gian Cruz (b. 1987, Manila, Philippines), is a multidisciplinary Filipino artist whose artistic practice is heavily rooted in photography, architecture and diasporic studies of Southeast Asian migrant communities in Europe integrated with his institutional work and background in art theory and criticism. For the 2019-2020 cycle; he became the first Southeast Asian participant in completing the Independent Studies Programme at MACBA. Furthermore, he is the first student of Asian heritage in its 18-year history.

His practice extends to performance, translation, history, architecture, ecology, cinema, HIV/AIDS activism and several other fields and contexts that engage with his current preoccupations as an artist. Over the years, he has worked closely with the National Museum of Modern & Contemporary Art, Korea, Jeu de Paume, Paris, The Museum of Photography, Seoul, La Biennale di Venezia, Visual AIDS, New York, 4A Centre for Contemporary Art, Sydney, and Casa Asia, Madrid; to name a few.

Gisela Marcelang (b. 1988, Manila, Philippines) is a writer and photographer merging both practices and a background in design and communications to trace connections, messages, and meaning through image- and zinemaking in today’s limitless digital and physical visual clutter. She was a participant at the 2013 Angkor Photo Festival Workshop in Cambodia, and was part of Namamahay, a collaborative archiving project by Kwago in Threading through the Eye of the Needle, the first Trans-Southeast Asia Triennal Reseach Exhibition Series at the Art Museum of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts.

A Critical Essay by Gian Cruz

I. PORTALS: CHAOS BECOMES CLEAR

For the Philippines, an archipelago geographically

fragmented, linguistically fissured, occupied not by one

but two invaders heralding a fierce but frayed republic

dominated by the oligarchic spoils of our split, postcolonial

selves—in a land tectonically and climactically doomed to

dissolution—for the Philippines, perhaps it is only through its

fictions that it can conceive itself a unity.

– Gina Apostol1

Portals allude to the literal and metaphoric tropes of gateways, doorways, entry points, passageways, routes taken consciously and unconsciously, or even fissures where one can be allowed entry… from the most evident to the most elusive ones. In this way, the idea of portals also properly represent a dynamic portrait of ourselves as Filipino artists seeking to properly define and present ourselves in our own terms, our own rightful timelines and dream as ourselves particularly resisting someone else’s definition of who we are instead of what should rightfully be our own.

The Filipino art critic and curator Marian Pastor Roces2exclaims that the Philippine identity is “an amalgamation of all those that came in passing” in the archipelago. Feigned with a series of colonial periods from Spain to United States to Japan; this then means there should be no hierarchy or distinction that those coming from European and other Western heritage are any better than the often denigrated animistic indigenous tribes and what exists in Southeast Asia as the largest concentration of Afro-descendant tribes in the Philippine archipelago.

We come to think of ourselves as an unconventional synthesis of these tropes of both the occidental and the oriental and turning the gaze within ourselves and enjoying the present maelstrom of chaos to enable us to unfurl our most authentic selves and see clearly… in a kind of rebirth, in a kind of repositioning or by all means the radicality of just embracing ourselves as Filipinos the way we’d like to perceive our newfound nationalism through the precarity of the visual image and the richness and incoherent materialities of our ancestors from all parts. In this sense, the gesture actively and consciously deflects or resists the comprehension and categorization of the spectator outside of our culture. It is not to alienate others different from our fissured selves constantly struggling to recollect a kind of unity in our postcolonial selves, we’d like to occupy this chaos and let this chaos lead us into seeing and thinking of ourselves ever more clearly. In such terms, we let the chaos transgress into a lucid state of clarity.

II. FISSURED ARCHIPELAGIC DREAMS (OR DREAMING AS OURSELVES)

Revisiting history finds this vexed actuality, which directs me back to our national hero José Rizal (1861-1896) and the looming nationalist sentiment during the final stages of the Spanish colonial epoch as illuminated by Resil Mojares in a chapter in Isabelo’s Archive entitled “José Rizal and the invention of a National Literature” which he says:

The issues Rizal faced at the close of the nineteenth century continue to challenge Filipino writers at the beginning of the twenty-first. To assert difference not merely for the sake of being different, but difference that meaningfully revises and renews not only how we Filipinos see ourselves but how others see us and themselves. To reconcile “internationalizing” and “nationalizing” positions: recognizing, on one hand, the danger of being absorbed and lost in the discourse of dominant others; on the other hand, the danger of being trapped in a conversation that does not open out into the world; in either case, the prospect of being barely visible in the world. To widen the social and material space that allows us to do our work and be read and heard (104).3

And this perspective permeates through the present outside of Filipino writers but also to artists and in the broader spectrum of cultural workers. Framing the timeline from the close of the 19th century to post-Marcos dictatorship (1986 – present) and the neo-liberal globalized space in the Philippines is rooted in this polemic brought about by Neferti Xina M. Tadiar in her seminal book Fantasy-Production: Sexual Economies and Other Philippine Consequences for the New World Order: “… or perhaps we have not been dreaming at all and instead, have lived in the rote mythographies of our given social identities” (5).4

In Portals, we try to rethink of ourselves as Filipinos taking who we are as something in constant flux and also with consideration from those other perspectives outside of our own and redefining a visual ecology and language in our own rightful autonomies and far away from the convenient or discernible tropes of a Euramerican art historical field particularly in the domain of photography. And as John Clark (well-known for his extensive work on Asian modernities) would add such contexts as mine alongside other Asian contexts are enmeshed in “an intellectual self-distancing from habitual modes of thought of practice… disruptive of comfortable art history within a received Euramerican frame.”5 And the Philippines in her Southeast Asian glory operates way beyond this frame but also subverts it with its transoceanic circumscribings and transgressively amplifying her connections through Europe in a refracted decolonial gaze by the activation of this synthesis of our multiple selves that is not purely Southeast Asian nor Hispanic and it goes far beyond that.

We disrupt in an affective way oscillating beyond the binaries and the literal and the figurative reinterpretations of our transoceanic states of being immersed in connection with Austronesia, the Sinic World and the rest of East Asia, Europe (by way of Spain), Latin America, the Carribean, the Malay World, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and South Asia.

Reclaiming the Filipino self-image within a global context attentive to the dynamic and loaded conditions brought about by the Filipino Revolution as the first exhibition of “successful transnationalization of Pan-Asianism, involving cross-political practice and revolutionary networking toward the goal of overthrowing two Western imperial powers” (Aboitiz 26) as elaborated in the crucial interventionist attempt by Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz in her book called Asian Place, Filipino Nation: A Global Intellectual History of the Philippine Revolution, 1887-1912. The Philippine revolution, which before the recent and more extensive scholarship of significant interventions in Southeast Asian histories has often been discussed as if it occurred in the Western world leaving behind that it, took place in Southeast Asia. Hence, CuUnjieng Aboitiz’s referring to it as the “Asian Philippine Revolution” becomes very fitting in this inquiry.6

III. FOR A PHILIPPINE ELSEWHERE: THE IMAGINATION OF AN INDISCERNIBLE AND ENDLESS ELSEWHERE

I,began,to,Die,and,I,began,to,Grow.

– José Garcia Villa, Divine Poems (134)

(from Doveglion: Collected Poems, 1941)7

The world is always in movement. People have everywhere at some time been dispossessed.

– V.S. Naipaul, Two Worlds (Nobel Lecture), 2001.8

Finally for the time being and not ultimately, the series in its current state seeks to initiate the spectator into the vicissitudes of the erratic and the uncertain present moment of finding oneself perfectly at home in the tumult of chaos or a plurality of voices or contexts. In a certain way, it is an invitation to a circumscribing of a non-distinct labyrinth one no one has heard of yet because it is in the present tense; in the present unknown; in the present of indiscernible elsewheres. And we find in this inquiry retracing the inherent essence of ourselves as Filipino artists working with contemporary photography and expanding it to the bigger spectrum of the contemporary art world not for the convenience of being made visible by a global network of platforms or institutions but working through the uncomfortable and often alien definitions of our own proper identities and boldly in the maelstrom of things come up as our own in these diverse set of portals. Each portal can allude to an aspect of the Filipino as fleeting and as unstable of all those who came in passing but it is like an active and safe space full of potential enriching this coalescence of our many postcolonial selves only beginning to only see it in more concrete decolonial terms.

Notes:

-

-

-

- Apostol, Gina. “Foreword.” The Woman Who Had Two Navels and Tales of the Tropical Gothic (by Nick Joaquin). New York, NY: Penguin Random House LLC, 2017.

- Marian Pastor Roces is a Filipina art critic and independent curator who writes about the various ways in which varying societies have deployed the concepts of culture, nation, and identity, and how these concepts fuse or clash upon the contact of these different societies. She has approached this subject from a variety of perspectives, including a long-term study of textile traditions of island Southeast Asia. She also takes a keen view of such relationships in studying the difficult links and disjunction between what is thought to be traditional art and what is thought to be contemporary art.

Pastor Roces’s theoretical work is published and read internationally. Her writing is informed by her parallel work as a curator. For the last 25 years, Pastor Roces has created the curatorial and management designs for the establishment of four major museums in several cities in the Philippines.

More: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/china/Marian.html - Mojares, Resil. “José Rizal and the Invention of a National Literature.” Isabelo’s Archive. Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 2013.

- Tadiar, Neferti Xina M. “Introduction: Dreams.” Fantasy Production: Sexual Economies and Other Philippine Consequences for the New World Order. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2004.

- Clark, John. “Knowing Modern and Contemporary Asian Art.” 4A Papers: Issue 7, November 2019: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

<http://www.4a.com.au/4a_papers_article/knowing-modern-contemporary-asian-art-john-clark/> - Aboitiz, Nicole CuUnjieng. “A Transnational Turn of the Century: The Asian Philippine Revolution. Asian Place, Filipino Nation: A Global Intellectual History of the Philippine Revolution, 1887-1912. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2020.

- Doveglion is a collection of poems by Filipino poet José Garcia Villa (1908-1997) and remains a significant reference for his contributions to both Philippine literature and the global literary scene at large as he was the only Asian poet among a group of modern literary giants during the 1940s New York alongside W.H. Auden, Tennesse Williams, and a young Gore Vidal and was known as the “Pope of Greenwich Village” (from Penguin Random House biographical note on José Garcia Villa).

- Naipaul, V.S. “V.S. Naipaul – Nobel Lecture: Two Worlds, 2001.” Accessed: 01 March 2022. Nobelprize.org

<https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2001/naipaul/25675-v-s-naipaul-nobel-lecture-2001/>

-

-