The Panther

Original by Rainer Maria Rilke

Translated, from the German, by Alex Buckman

In the Jardin des Plantes, Paris

His gaze is from the passing bars so weary

That now, within it, nothing more is held.

For him there are a thousand bars to see

But then behind a thousand bars, no world.

His pacing strides wind circles ever smaller,

And to the beating of a distant drum,

Perform a dance of power ’round a center

In which a once-so-mighty will stands numbed.

Now and again, the pupil’s curtains part

Without a sound. An image enters in,

Flows through the hush of tensely coiled limbs,

And vanishes within the beating heart.

Der Panther

Im Jardin des Plantes, Paris

Sein Blick ist vom Vorübergehn der Stäbe

so müd geworden, dass er nichts mehr hält.

Ihm ist, als ob es tausend Stäbe gäbe

und hinter tausend Stäben keine Welt.

Der weiche Gang geschmeidig starker Schritte,

der sich im allerkleinsten Kreise dreht,

ist wie ein Tanz von Kraft um eine Mitte,

in der betäubt ein großer Wille steht.

Nur manchmal schiebt der Vorhang der Pupille

sich lautlos auf -. Dann geht ein Bild hinein,

geht durch der Glieder angespannte Stille –

und hört im Herzen auf zu sein.

Rainer Maria Rilke was an Austrian poet and novelist born in 1875 in Prague. His first great works were “Das Stundenbuch” (“The Book of Hours”) (1905), “Neue Gedichte” (“New Poems”) (1907) and “Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge” (“The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge”). Rilke traveled during his lifetime to Italy, Spain, and Egypt among other places; but Paris was central to his poetic career. Rilke spent the final years of his life in Switzerland, which is where he wrote his last two works, the “Duino Elegies” (1923) and the “Sonnets to Orpheus” (1923). Rilke died of leukemia on December 29, 1926. His work was well-regarded in Europe at the end of his life, but his reputation grew even more following his death, and has come to be widely appreciated. (Adapted from poets.org).

Alex Buckman is a fourth-year student at Bard College pursuing a double-major in German studies and bassoon performance. Alex is especially interested in German grammar in the context of translation, and will begin a thesis exploring these topics while studying abroad at Humboldt Universität in Berlin in the summer of 2023.

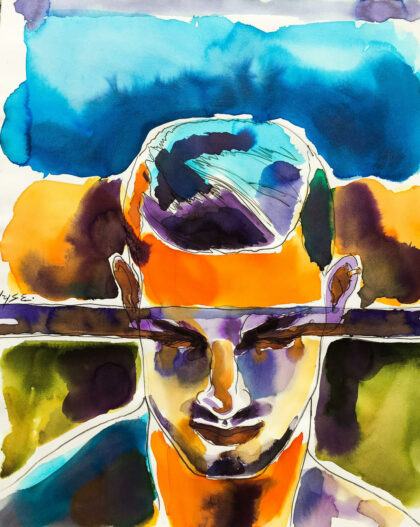

Internationally collected artist Richard Vyse has shown in galleries in Manhattan, Boston, Honolulu, and Paris. He has studied at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan and taught at Pratt in Brooklyn. His art has been featured in many international art magazines. His art is in the Leslie Lohman Museum in Manhattan. “Celebrating man in line and spontaneous brush strokes to capture a moment and a mood.” To read full bio or view published and sold art, visit: https://manartbyvyse.blogspot.com/. To view artist on Instagram, visit: https://www.instagram.com/artbyvyse/.

Translator’s Note:

Rilke’s “Der Panther” succinctly and profoundly explores what it means to be stripped of one’s physical autonomy, and how physical captivity affects a living being psychologically. What stands out the most to me is how subdued the imagery of the work is. The poem does not describe any violence and uses graceful, beautiful language, but it still conveys the brutality of the panther’s loss of autonomy. The panther’s will, its inner life force, has been incapacitated, leaving it physically alive but brain-dead — and from the panther’s perspective, the entire world beyond its cage has died as well. This loss is almost unimaginable in scale, and yet from the outside it is nearly invisible. A lack of autonomy can look calm or even captivating to an outside viewer, and nevertheless be devastating. This quieter, more easily overlooked form of violence is what Rilke urges us to examine. Instead of creating a visceral image that confronts the reader with the physical, external horrors of captivity, Rilke draws us further into the panther’s mind with each stanza. The poem sinks into our minds softly and slowly, yet deeply, reflecting the panther’s loss of autonomy, which appears calm but has destroyed its inner self and its entire world.

To preserve the rhythm and rhyme scheme of the poem I had to make several changes, most notably at the beginning of the second stanza. The beating drum is not an element of the original work, but rather the result of a series of decisions I made concerning the surrounding lines. I found that “numbed” was the translation of the adjective “betäubt” that best conveyed the passive violence the panther experiences. Other possibilities, such as “stunned,” “stupefied,” or “drugged,” imply a more active and physical conflict, and would disrupt the hushed restraint of the work as a whole. The preservation of this tone was my priority in translating the work, so I was willing to make adjustments to accommodate the use of “numbed”. Thus, I needed to use a word in the second line of the stanza that rhymes with “numbed”. Additionally, I condensed the content of the first two lines of Rilke’s second stanza into just one line in order to fit the desired rhythmic pattern. I needed an image to connect that content with the “dance of power” in the stanza’s third line. The beating of a drum in the distance expands on the motif of the dance, and is another sensory representation of the muted strength of the panther. The reader can sense the power inherent in both the drum and the mighty will of the panther, but they are so stifled and faded that we only know them by the far-away echoes of their former glory.